Nikkei Asian Review, 12 April 2023

Mizoram, India — A sudden chill stirred three pregnant refugees as the sun disappeared behind the mountains of Mizoram state, on India’s northeastern border with Myanmar.

Sitting outside their makeshift home, a tarpaulin tunnel sheltering 160 people, Then Nun Mawi said she had suffered cramps so bad that she sought a doctor, who offered a vitamin injection. “But I couldn’t afford it,” said the 33-year-old. “I am bleeding.”

Surviving on donated rice and mustard growing around the camp, the other two women said they had no cash, and would probably see a doctor only on the day of delivery. “I can’t check my health or properly take care of myself,” said Baui Uk Ting, 29. “I haven’t taken any medicine during this pregnancy.”

The women have all crossed the border into India from Chin state, one of Myanmar’s poorest areas, which has been plunged into violence by the country’s military takeover on Feb. 1, 2021. The three escaped the violence with no belongings, hoping to find help.

Away from the front lines in Myanmar’s civil conflict, a battle is raging to save mothers and their newborns, who are scattered across remote hills inside Chin state, hemmed in by government forces or languishing on the border with India without access to health care.

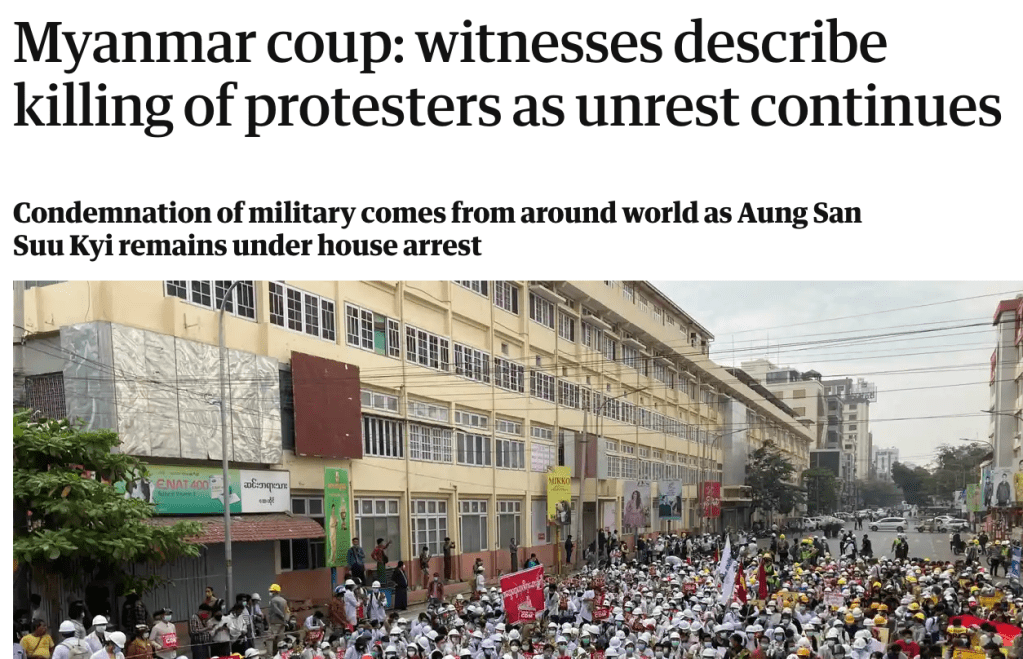

In Chin state, ethnic Chin used hunting rifles and intimate knowledge of the rugged terrain to resist the military junta. Unable to quash the resistance, the military massacred civilians and bombed towns.

So far, the violence has displaced 44,000 people in Chin state and pushed a further 51,600 into the neighboring Indian states of Mizoram and Manipur, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the U.N. refugee agency. In what has become a revolution that may define the country for generations, an estimated 1.37 million people have been driven from their homes throughout Myanmar, according to the U.N.

In Mizoram, a group of four tireless midwives delivers about two babies a day at a small clinic overlooking the Tiau River, which marks the India-Myanmar border in the region. Nikkei Asia is not naming the clinic and has changed the names of its staff and other medical personnel because of security concerns — some of the midwives fled fighting in their hometowns and have family in the resistance.

But the clinic’s name is known among refugees grateful for its free neonatal care, among them a woman who was rushed in during reporting for this article. After delivering the baby, chief midwife Mary, 30, said internally displaced people and refugees arrive at all hours at the clinic, where she and her colleagues make do with limited equipment as gunshots ring out sporadically a few hundred meters away in Myanmar.

“If people come in from the Myanmar side, and I have the medicine, I treat them for free, which makes me proud, like God has given me a chance to help them,” said Mary, an ethnic Chin. “I want to develop this clinic and build more to take care of my people.”

In the absence of an incubator, newborns are wrapped in towels and their mothers are carried by hand, intravenous drips attached, to rest in bare rooms. Some babies are born with jaundice, which Mary puts down to malnutrition and sometimes alcoholism.

“Most women in Chin don’t get enough food,” she said. “They work all day in cultivation using their bodies, but maybe twice a week they get milk and meat.”

The clinic is expecting a wave of cases involving mosquito-borne infections with the arrival of the monsoon, probably in June, and it receives dozens of conflict-related injuries during fighting across the border. But it mostly serves women among the 5,000 refugees who live in surrounding camps of corrugated iron and wooden slats, which sit between the river valley and houses on the steep slopes above.

While New Delhi has seemingly prioritized relations with the Myanmar regime, the Mizoram government and the local Mizo people have supported the Chin refugees, with whom they share an ethnic kinship and the Christian faith. The Chin and Mizo worship together in churches and, on the winding roads, in trucks that pause so passengers can pray that they will not topple over the cliff edge.

Without routine vaccinations or consistent schooling, faith is playing a large role inside Chin state as well. Clean water and sufficient food can be difficult to access, and the military presence creates a pall of fear that hangs over the wild orchids. Soldiers often detain health workers and confiscate medical supplies at roadblocks, said a leading doctor in a Chin health care group. The doctor asked for names to be withheld to protect the group’s cross-border work.

The Chin group said it had delivered 543 babies in the resistance-controlled areas of Chin state between April and December 2022 and counted about 3,800 pregnancies in the area in July 2022.

Milk powder or sugary water are substituted for breast milk when displaced mothers stop lactating because of stress, illness and malnutrition, said the doctor, exposing the babies to illnesses. Although statistics were unavailable, she added that reports of miscarriages and premature births have climbed as the health system collapses.

“I myself had two consecutive miscarriages in 2021 after the coup while I was in the village hiding from the military after I joined the CDM,” said the doctor, referring to Myanmar’s civil disobedience movement.

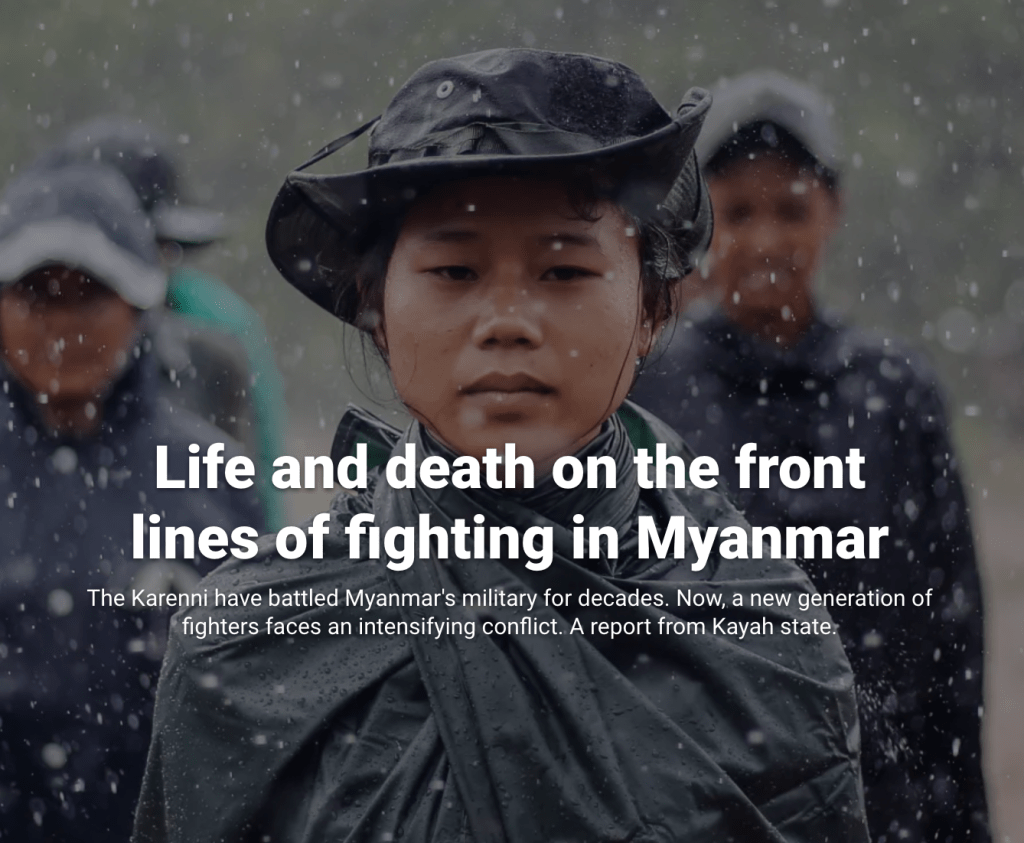

Teams of midwives and doctors who were vital cogs in the health care system before the military takeover now ride motorcycles from village to village in resistance strongholds, supporting pregnant women who fear the arduous journeys to hospitals in urban areas that are controlled by the regime.

Speaking over the phone from a resistance-controlled village, Dr. Za, 32, said “things are a lot worse” than before the takeover. “The midwives in the villages have no medicine or equipment, so some have changed their jobs to sell food or do something else,” he said.

Alongside four midwives and an assistant surgeon, Za said the group delivers about 20 babies a month, although sometimes they are too late. “Some people call me for help, and then after some minutes, call me again to say that the mother and child have already died,” he added.

Za said he had seen outbreaks of measles, malaria, gastroenteritis and spinal tuberculosis in villages reachable only via neglected roads that can be unpassable in the rainy season. In early March, he said, he tried to remove a leech from inside the nose of a pregnant woman that came from the village’s water source.

“The water is not clean throughout much of the countryside,” he said. “She was already weak. I tried my best to remove it, but it would not come out.” Za said he is sourcing quinine nasal spray, which he hopes will remove the leech, and plans to return to the village to treat the water.

Another patient who was in labor for three days traveled for a caesarean to a hospital three hours away in Hakha, the military-controlled Chin state capital. But soldiers at a checkpoint opened fire at the car during a clash with resistance forces, and she was forced to turn back to her village.

“By the time she got back, it was 11 p.m. and within half an hour we had started the generator and it was time to operate,” said Za, adding that the operation would have been much safer at the better-equipped hospital. The mother survived, he said, and the baby was recovering after being treated for asphyxiation.

In another case, two nurses were tending a birth in the town of Rezua when soldiers burst in and took the nurses to their base to treat their wounded, he said. The pregnant woman was also taken but died at the base.

“The soldiers did not allow the family to see the body for three days, and even then, they told the family they couldn’t bring the body back to the village. They had to cremate her where the soldiers were,” he said.

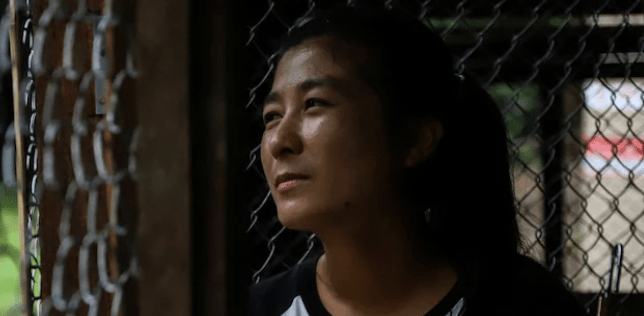

On the Indian side of the border, Phirlian Mawi, 28, described her ordeal of escaping soldiers in Chin state before eking out a living in a refugee camp. Despite the stress, she was excited. Her baby is due in May.

“Before the coup I had three miscarriages, but this time I became pregnant,” she said. “I am so happy about that. I wish in my prayers that my baby will become a missionary for the Kingdom of God.”

Additional reporting by Pu David.