Nikkei Asian Review, 24 November 2024

MYANMAR BORDER, Thailand — The sudden escalation of Myanmar’s civil war, with coordinated resistance attacks across the country’s northeast, has shaken the military establishment and reenergized pro-democracy forces. Rare interviews with wives of serving soldiers reveal that the grip of the dictatorship may be as shaky in its bases, away from the front lines, where anxiety is deepening among military families.

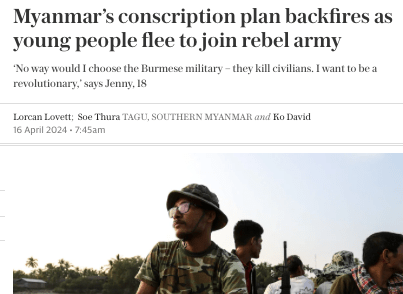

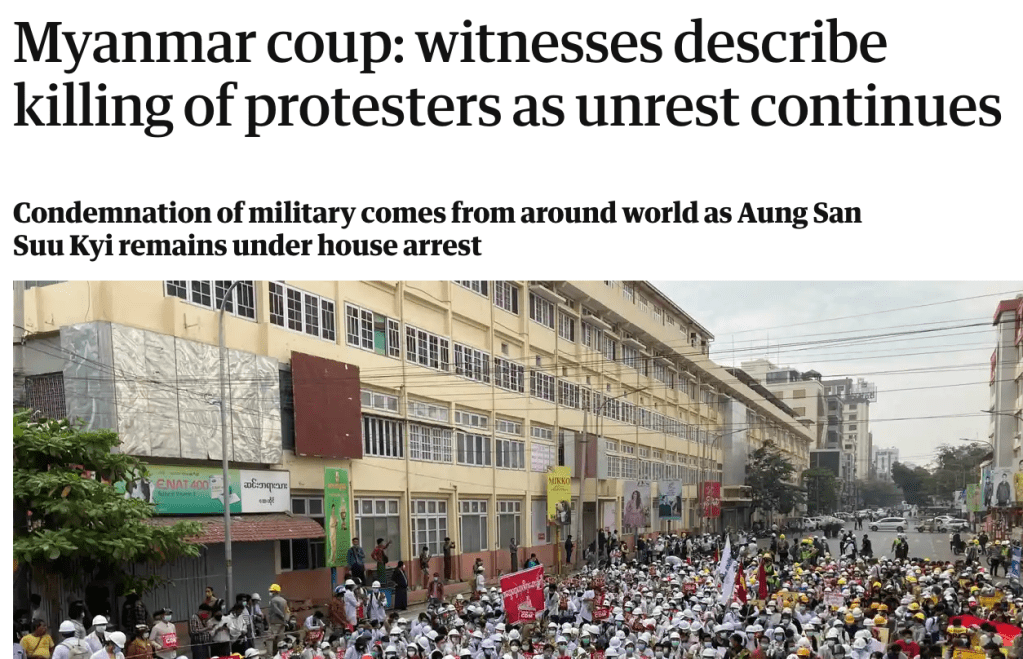

In what opposition forces term “Operation 1027,” named for the date it began in late October, key resistance groups overran army positions in northern Myanmar, seizing control of two border trading posts with China. In unprecedented joint operations between various ethnic armed groups and guerrilla-style people’s defense forces, they moved on to take more than 150 military posts as well as government facilities in Shan state.

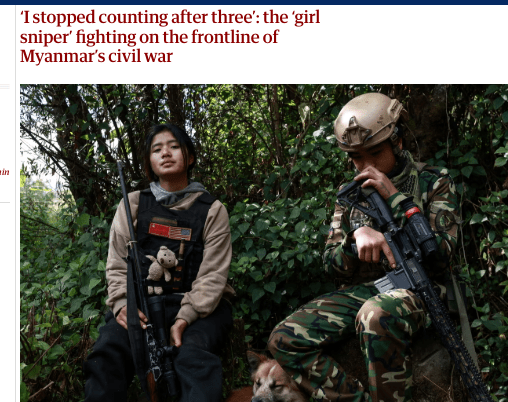

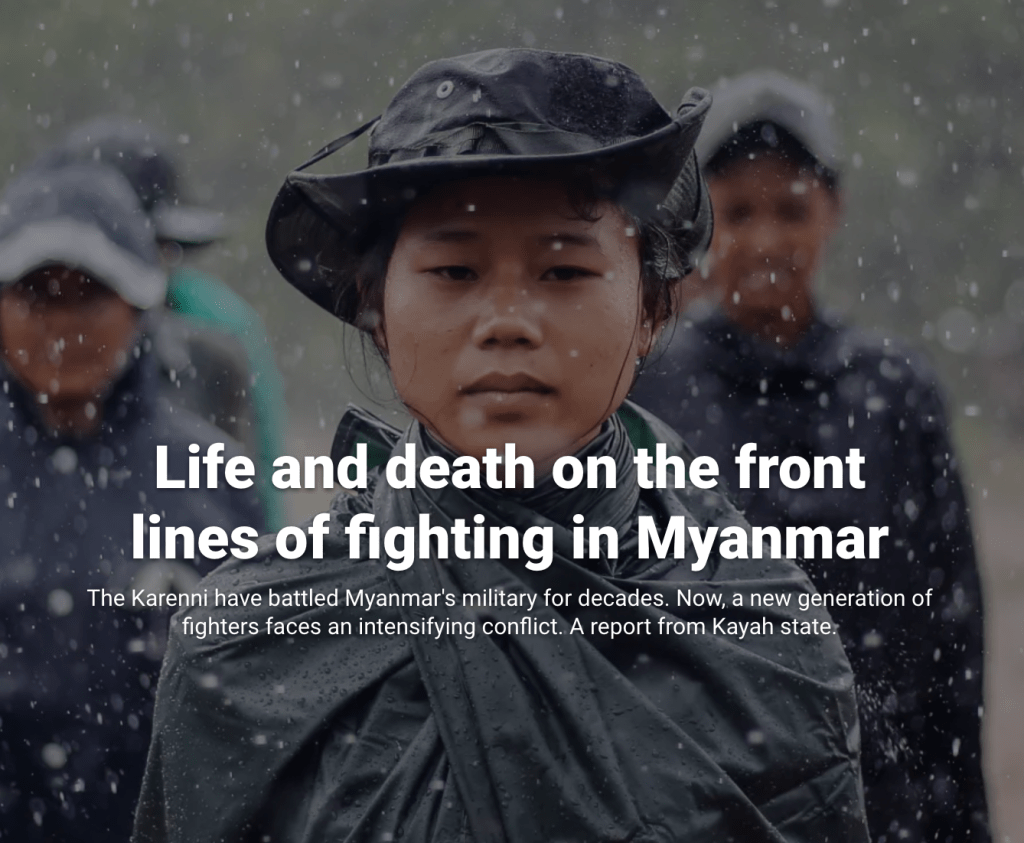

Signaling rare coordination, other forces across the country launched their own attacks, among them the ethnic Karenni resistance who edged closer to capturing the capital of Kayah state, Loikaw, near the border with Thailand. By mid-November, a coalition of groups in central Myanmar had claimed victory in Kawlin, a town in the Sagaing region, while ethnic fighters raised the Chin flag on the border with India.

The impact on military forces inside Myanmar has been profound — echoed in the testimonies of military wives.

Defined by a hierarchy that mirrors their husbands’ ranks in the notorious institution, the spouses whisper about desperate losses as their wartime duties expand to patrolling military compounds in the absence of soldiers and chanting Buddhist mantras believed to protect the troops of an army accused of countless atrocities.

Two women inside such compounds at undisclosed locations in southern Myanmar told Nikkei Asia about sinking morale. Their responses — handwritten notes photographed and sent by phone, as well as interviews with military wives in exile with their husbands — depict paranoid lives and resentment toward higher ranks.

“Soldiers’ wives and adolescents are being pushed more to take on patrol duties,” wrote Sandar, the wife of an army sergeant, on Nov. 17. Her name has been changed for safety.

“Military families are feeling more insecure. They don’t trust each other and are afraid to … die,” she wrote.

She said officers at her compound admitted the military had sustained “many losses” since the launch of Operation 1027, while inflicting “a lot of kills on the rebel side every day.” With growing pressure from the leadership, “there’s arguing among the officers and unclear orders.”

Myat, the wife of another sergeant, wrote that military spouses were set to undergo more combat training on Nov. 19 to defend their compound. “The soldiers’ families are cursing the officers who don’t care about the private soldiers,” wrote Myat, also a pseudonym.

After arresting the country’s elected leaders and seizing power on Feb. 1, 2021, chief commander Min Aung Hlaing’s troops brutally suppressed peaceful protests against the military takeover, while the generals dragged millions back into poverty. Myanmar’s economy contracted by 18% in the year after the coup. It has since registered around 3% annual growth, according to the World Bank, which also warned in a June 2023 report of “permanent” economic damage from distorted policies and the prolonged turmoil.

Now, an increasingly well-coordinated armed insurrection that stretches from Myanmar’s northern mountains to its coast on the Andaman Sea threatens to overthrow the regime.

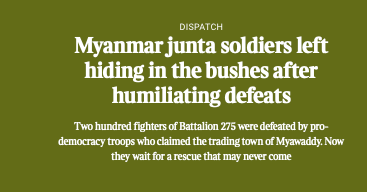

Min Aung Hlaing made his first public response to the offensive on Nov. 2, when he vowed to carry out counterattacks against the ethnic insurgents. In a rare convening of the National Defence and Security Council six days later, he said the military had “successfully regained control of the situation,” only for a new front against the military to emerge within days in western Myanmar’s Rakhine state. Although the regime can damage resistance forces with punishing airstrikes, ambushes and the destruction of several key bridges have hindered its troop movements.

Min Aung Hlaing’s support base in the military is limited to those tapped into his patronage, wrote Sandar in a separate round of correspondence, weeks before Operation 1027. “Many soldiers from the compound have died [in the conflict], but we are not told the details,” she said. “Many in the compound are injured as well.”

She estimated that “about 90% of people from the army don’t like Min Aung Hlaing.”

“He knows the situation and I want him to solve the problems so things can become normal,” she added. But she lamented that “no one cares” about the deaths of privates, whose families are “the grass between the buffaloes,” referring to the military and the resistance.

Estimates for the military’s strength are a source of debate, but some believe that casualties, desertions and defections have reduced the number of combat troops to 100,000 to 120,000. The pro-democracy parallel government, the National Unity Government (NUG), says that its armed wing, comprising people’s defense force fighters, has 65,000 members, while independent local forces, urban cells and ethnic insurgents are thought to number in the tens of thousands.

Interviews with dozens of defectors suggest that common soldiers operate in the field with inadequate rations and basic equipment. Army recruits are often poorly paid and abused by officers.

Groups run by military defectors estimate that 4,000 to 5,000 soldiers as well as around 9,000-plus police personnel have fled to join the resistance since the 2021 takeover. Since the launch of Operation 1027, at least 500 more soldiers have defected, but many more have simply deserted, said Maj. Naung Yo, of People’s Goal, the largest defector support group.

“Mentally and emotionally, they feel like the Tatmadaw is crumbling — particularly in the north,” he said, using the armed forces’ Burmese name. “Even those living in bases are feeling the impact of the conflict as they learn more about the junta’s failures and the abuses they commit, also against their own soldiers.”

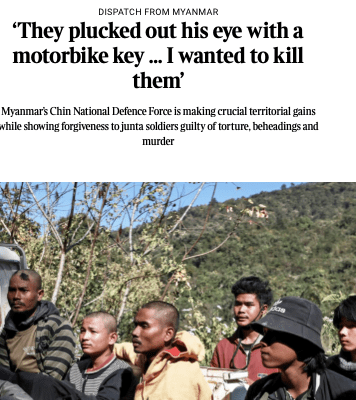

Those inside the military system can expect little sympathy from a broader public subjected to torture, killings and arbitrary arrests. The military relies heavily on fighter jets and helicopter gunships imported from Russia and China to put down resistance, and its ground forces have carried out arson and sexual violence, according to witness accounts. Observers describe the military, mostly soldiers from the ethnic Bamar majority, as a brutalized force indoctrinated with a sense of superiority over the country’s minorities.

Still, Myat wrote that the military brass were duping soldiers into believing they were being stationed in relatively safe cities, but then delivered to the front. “Most of the soldiers I know are depressed and their formations are unstable,” she wrote. “Of course, the army has done many cruel things. The duty of the army should be to protect the country, not to destroy and kill its people. I want to have a democracy.”

For spouses and families, movement restrictions coupled with fear of the outside consign most to the secluded world of their compounds. The use of mobile phones is often restricted. Login details for social media accounts must be shared with the compound’s head office, said the wives. Some women use mobile calls to relatives outside as a source of news.

If deserting soldiers are captured, they risk a prison sentence, torture or possible execution, according to defectors, while their family members are exposed to retaliation. Yet some families do cut ties with the military despite the danger.

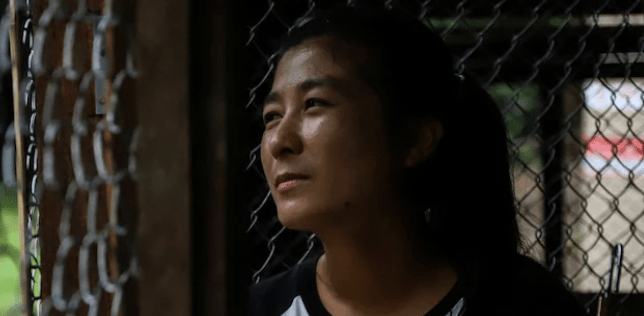

When her husband defected in August 2022, Kyi Pyar Win, 48, was questioned by the commander at a compound in southeast Myanmar where she had lived for six years alongside over 300 adults and children. Denying any knowledge of her husband’s plan to switch sides, she was given five days to leave. She said the other wives labeled her a “red bitch” — the color of the National League for Democracy, whose elected government was ousted by the military.

In an interview at a safe location along the Thailand-Myanmar border, she said the spouses of lower ranks were subjected to abuse and competed to ingratiate themselves with the upper echelons. “The wives don’t like each other and are always taking digs at someone else’s mistake,” she said.

At social events, officers’ wives “feast on plates of food” while privates’ wives share from a large steel bowl and do all the washing up, she said. Children of lower-ranked personnel are bullied and teachers favor the officers’ children, she added.

With the compounds drained of privates, the wives do chores and stand guard with guns.

“While the families of the commanders slept, we patrolled, worried and stressed,” Kyi Pyar Win recalled. “One night, someone shot at the gate of the compound and the guards — the soldiers’ wives — ran at top speed to their homes. They did not think about fighting.”

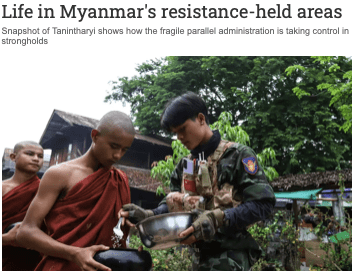

As conditions deteriorate, faith is not optional. Inside the compounds, commanders are turning to astrologists to direct Buddhist prayers. If a wife cannot join, she must pay for a replacement, Kyi Pyar Win explained. Each chant begins with the name of a particular battleground and lasts up to two hours.

Because of the mantras, “the wives know earlier than others where the front line is and how many soldiers are there,” she said. Hallways are sometimes lined with flowers, candles and glasses of water leading toward the figurine of Buddha.

In the early days of the takeover, when demonstrators took to the streets chanting “Motherf—– Min Aung Hlaing,” the military tried to counter the mass protests with its own rallies in which civilians were reportedly paid 5,000 kyat (about $2.40) to participate. “But we had to do it for free because we are soldiers’ wives,” said Kyi Pyar Win. “If someone from the group shouted, ‘Senior General Min Aung Hlaing,’ we had to follow with, ‘May he be happy, may he be healthy.’ I was really depressed and ashamed.”

It soon became too dangerous for anyone — pro- or anti-military — to demonstrate in the cities. After soldiers began killing unarmed protesters, public fury scared military spouses away from shopping in local markets.

Living on her husband’s salary of 160,000 kyat, Kyi Pyar Win said she turned to the military compound store, which was named “Cheap Price Shop” but sold rotten eggs, hard rice and sandy fish paste at inflated prices.

“Whether you take the food or not, they cut the cost from our salaries, so we took those rations and shared with some other families,” she said.

Officers spread rumors that defectors would starve to death in the forest or face being buried alive by the armed opposition. Kyi Pyar Win believed them, expecting revenge for the screams of prisoners tortured at the compound. Describing the abuse of a doctor accused of treating PDF fighters, she said his pleading was “a living hell that gives me nightmares.”

“I imagined that when my husband defected, he would be tortured like that,” she said.

But when her husband video called after his defection, he smiled, turning the camera on his comfortable accommodation and food. She soon joined him and has encouraged other military families to follow.

“They know about the military killing civilians,” she said. “But they are silent and afraid.”

Additional reporting by Gwen Robinson, editor-at-large; Ko David on the Thailand-Myanmar border; and Yucca Wai.