Nikkei Asian Review, 14 April 2024

In a small workshop in western Thailand, Aung Tin Tun puts the finishing touches to a plastic hoop created by a 3D printer. Filing a stubborn barb of filament, he explains that the hoop will be the grip of a prosthesis that can be attached to a garden hoe, allowing a local grandfather who lost his arm in a chaff cutter to loosen soil and grow vegetables.

“I want to be an arm for people who need one,” says the 39-year-old 3D printing manager. “Everything comes from their ideas and feedback.”

Aung Tin Tun works for the Burma Children Medical Fund, a nonprofit organization based in Mae Sot, Thailand, which is primarily focused on helping children who need surgery or complex medical care, sometimes as a result of the political turmoil in neighboring Myanmar, now in its fourth year of civil conflict following a military takeover on Feb. 1, 2021.

Based in the compound of the Mae Tao Clinic, a well-known medical center, the BCMF team says the spike in demand has fueled their creativity and raised the quality of their custom-fitted prostheses.

From a simple strap with a holder for a spoon or toothbrush to an arm-and-torso device comprising over 100 parts, the organization’s prosthetic devices have evolved significantly since it began using 3D printers in 2019. Three of its seven printers were purchased last year with support from the Switzerland-based Brodtbeck Philanthropy Foundation.

The BCMF got its start arranging surgery for children in the Thai-Myanmar border area in 2006, says its founder, Kanchana Thornton, before expanding into eye screenings and wheelchair sourcing. Then Kanchana saw a BBC clip of a British man using a 3D printer to make prosthetic hands, realizing instantly how such a hand could help a young disabled migrant she had befriended.

The British man told her how to find online instructions for 3D printing, and a friend in Australia offered to fund the initiative. Noticing the steady increase in Thailand’s western border region of amputees who had lost limbs due to accidents, conflict, disease or congenital birth defects, she quickly expanded output, and the clinic has since produced about 70 prostheses, she says.

One of the first recipients of a 3D-printed prosthetic hand, a former member of the Karen National Union, a Myanmar ethnic armed group, went on to connect the BCMF with others in need from communities in Karen state. The latest tweak of his own prosthesis featured a guitar pick holder, says Kanchana, a former nurse who came to the Mae Tao Clinic as a volunteer in 2001.

“He really missed playing guitar,” she says. “It made him happy when he was sad, but he couldn’t do it, so we printed a guitar pick.”

Kanchana is hoping to increase output of prosthetic hands significantly this year. Producing 3D prosthetic legs is currently beyond the BCMF’s technical capabilities, but the group is seeking a partner to help broaden its output to deal with soaring demand, not least from the effects of land mines and cluster munitions used by the well-armed Myanmar military.

In December, UNICEF said that land mines and explosive remnants caused 858 casualties in Myanmar in the first nine months of 2023, while Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, a Switzerland-based nongovernmental organization that tracks the use and impact of such weapons, said injuries or death from land mines have now been recorded in every state and region except the capital, Naypyitaw.

The military, resistance forces and other armed groups have all used land mines, in spite of international attempts to ban the weapons, which Myanmar and many other countries have rejected. Although official statistics are not available, the group says that at least 96 townships were mined in 2022.

Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor also reported that the Myanmar military has attacked several parts of the country with cluster munitions since the takeover. These weapons are banned under an international convention signed by more than 100 countries, but are still used by the U.S., Russia, China, Myanmar and other nonsignatories.

The relatively low costs and accessible training involved in 3D printing could be of widespread benefit to the Myanmar population, but Kanchana says the production of 3D prostheses can be tricky, with some pieces requiring 24 hours of printing as well as the right temperature, filament, and consistent electricity.

The process starts with an accurate measurement of a residual limb, which forms the basis of a computer-aided design that is uploaded to a memory card and inserted into the printer. Not everyone can travel to the workshop to be measured, so the BCMF has a small team operating inside Myanmar, using portable printers that can run on solar energy during power cuts and operate discreetly to avoid detection and arrest.

“Some patients cannot come [to the Mae Tao Clinic] or cross the border so it’s our responsibility to help them,” says Myint (not his real name) during a visit to the border. “We box up the 3D printer and cover it if we have to move it, otherwise we may get asked questions if they see it.”

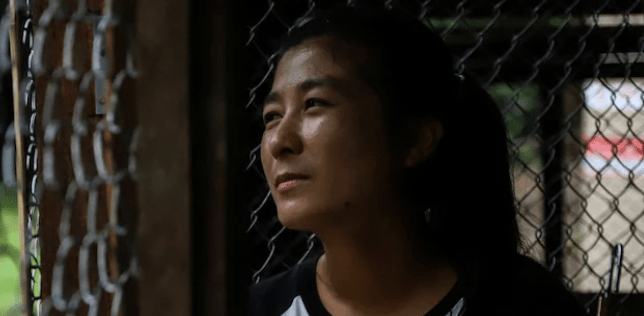

Near the workshop, the team checks in on Chan Thar, 25, a librarian who speaks English, Burmese, Thai and Karen. Chan Thar was born with one arm and one leg in Karen state, where, without any prostheses or a wheelchair, he would “pull myself along” on the ground, he says, using his able hand, until “step by step my teacher showed me how to use crutches.”

The thought of appearing as a “fat body” on the ground made him “very sad,” he says. “When I got this one, I stopped feeling like that,” he adds, showing a 3D arm prosthetic he received six months ago. “It has changed my life. I can do everything — cook, hold a phone, move a chair. The only thing that I cannot do is ride a motorbike.” Aung Tin Tun is working on a 3D-printed hand grip that could solve that problem.

Another recipient, 6-year-old Chit, needs replacements for worn-out ankle braces. Chit has a congenital spinal deformity which impairs her walking, so she holds her mother’s hand for support and tentatively tests the new, padded braces that have been strapped to her leg. Then she lets go. Standing on her own, she — and the braces — have passed the test. A bulging cheek of candy shows proof of reward.

“I’m happy to see my daughter walk,” says her mother, Ei Ei. “Without [the braces], she does not have the confidence to stand.”

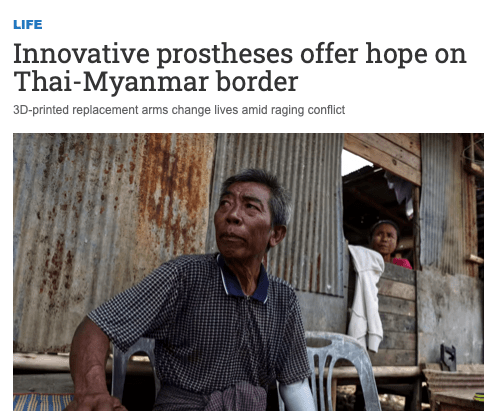

Aung Tin Tun finishes his day delivering the newly made plastic hook to Thein Soe, 56, a native of Myanmar’s Bago region whose livelihood as a cowherd in Mae Sot was devastated when he tried to free grass stuck in a cutting machine in February 2023. “After I lost my arm, my old boss didn’t think I was capable of working,” he says. A BCMF volunteer saw him and brought him to the workshop last summer.

With three grandchildren relying on his support, Thein Soe plans to grow vegetables in the patch of scrubland in front of the shack that he built for his family — if not to sell, then to eat. “I hope I can do my own farming as I don’t think anyone will hire me,” he says. “I like this one with the hook already. It’s better because now I can dig.”

Back at the workshop, Kanchana is pondering taking BCMF further toward cutting-edge technology. Her current dream, she says, is “bionic hands with electric nerves to move fingers.”