TANINTHARYI TOWNSHIP, Myanmar — The fading banner of Aung San Suu Kyi has seen better days. Riddled with bullet holes, it hangs outside the office of Myanmar’s National League for Democracy in Le Thit, a half-abandoned village on the banks of the Tanintharyi River in southern Myanmar.

The NLD office was vandalized two years ago by troops loyal to Myanmar’s military government. But they reserved lighter treatment for an image of Suu Kyi’s father, Aung San: a trace of gunfire next to his cheek, as if the soldiers lost the nerve to disfigure the founder of Myanmar’s military.

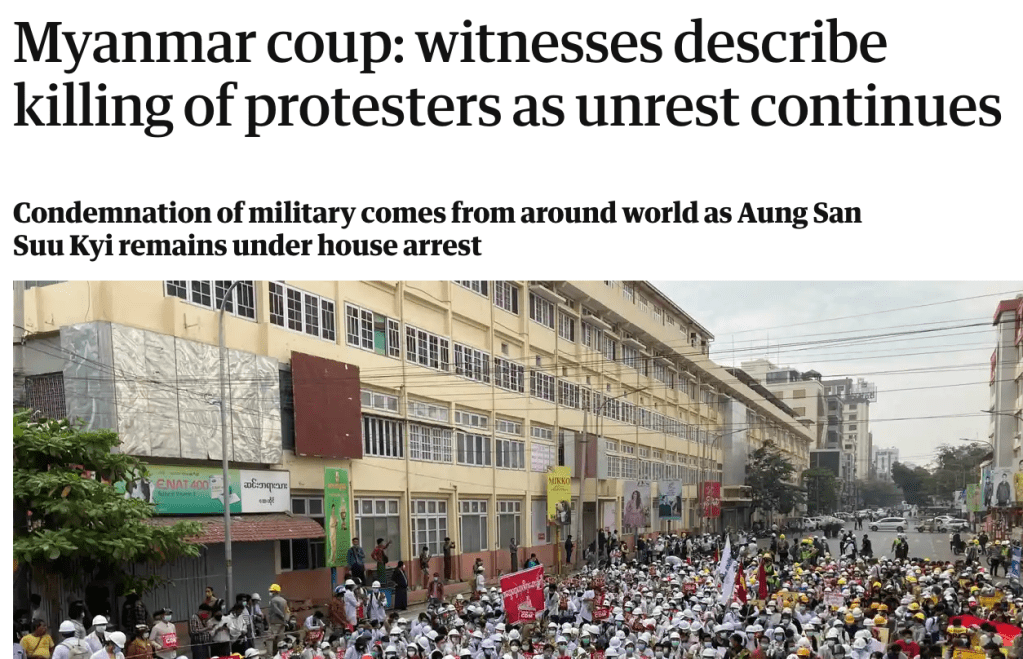

Hardy residents who remain in the village say the presence of local armed resistance forces has discouraged ground attacks, restricting regime troops to shelling their pockmarked homes. In March last year, a mortar blast killed a small child and injured eight other people.

Le Thit lies at the edge of a wedge of resistance territory that arcs across Tanintharyi township. On the opposite corner of the zone, in Tagu town, the scars of war are more discrete: the unkempt home of a military informer who skipped town, a hospital abandoned amid the threat of airstrikes, the hidden agony of mothers grieving for their dead children.

In the Tanintharyi area, as in resistance strongholds elsewhere in Myanmar, the regime has lost the countryside but still controls the larger towns, including Tanintharyi town and Dawei, the regional capital. In the township, a form of NLD governance has emerged in the shape of the National Unity Government, despite the official dissolution of the NLD by the regime.

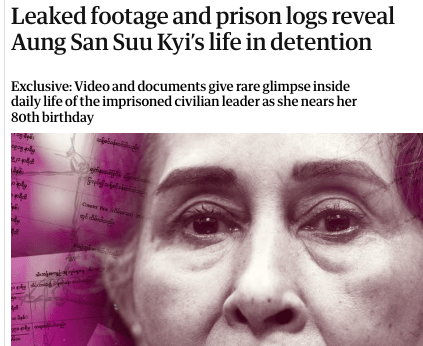

The NUG almost immediately proclaimed Suu Kyi its figurehead leader, ignoring her imprisonment by the generals in Naypyitaw when they seized power on Feb. 1, 2021. It is unclear whether the 79-year-old ousted leader knows that she is nominally the vanguard of a sprawling revolution.

To see how NUG governance is working, Nikkei Asia interviewed leaders of the resistance administration in Tanintharyi township, which is mostly divided between Myanmar’s oldest ethnic armed group, the Karen National Union (KNU), the NUG and the military regime.

The word “unity” in the administration’s name was chosen to build broad support for its campaign against the regime, distancing the organization from the perception that the NLD is dominated by the Burman ethnic group, the largest of Myanmar’s many ethnic communities.

But with NLD hands on the steering wheel, doubts linger about the NUG’s commitment to profound change, beyond toppling the dictatorship. For minority communities, restoring a nucleus of ethnic Burmans to power is seen as a risk that could perpetuate ethnic animosity and violence.

The NUG has different problems in liberated Burman-majority areas: a struggle to exercise ground authority, alongside a mushrooming of newly armed militias and, in some areas, persistent tensions between the NLD and ethnic minorities. As revolutionaries in Tanintharyi attempt to overcome their differences and counter a desperate regime, the region is a microcosm of the troubles that lie ahead.

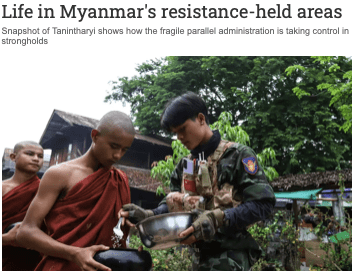

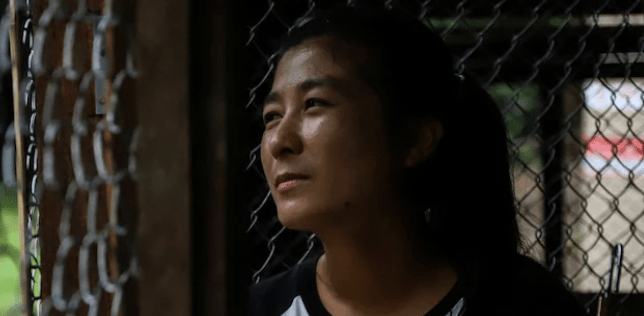

In Tagu, Si Si, a former NLD lawmaker who oversees local public security sits beneath the flag of the NUG’s armed wing, the People’s Defense Force (PDF), at the fire station, now repurposed as a jail. Her cheeks are smeared with a traditional ground bark paste called thanaka, believed to act as a sunscreen. She delivers her words firmly, her quiffed hair jolting as she speaks.

“We started our revolution to take down the junta because we don’t want a dictatorship, but no one is perfect, or perfectly educated, so … sometimes we have to set rules and regulations,” she says, referring to an NUG code of conduct for post-takeover forces.

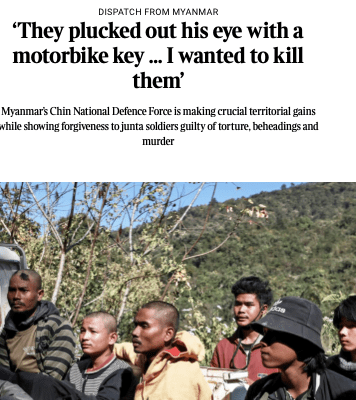

But the rebel administration has sometimes found it difficult to enforce its rules. Two PDF leaders in Launglon township were investigated for overseeing a September 2023 mission in which seven civilians were killed, allegedly for being regime informants. But the two leaders evaded the investigation by resigning from the PDF and forming an independent force, the Ba Htoo Army, which then abducted three professors from Dawei Technological University.

“It’s been hard to shape the movement that we want,” says Si Si. “But we have left our families and belongings. We move forward with determination.” Si Si adds that resistance administration budgets are tight, based on donations and taxation, while semi-automatic rifles and ammunition remain in short supply.

Nine male prisoners are detained in the fire station, including suspected thieves and an alleged military informer. Six barefoot men sit in one cell while three others stare out from the darkness of a sun-starved room. Wardens — a team of 10 — say prisoners eat food sent by their families or pay 5,000 kyat ($2.39 at the official rate, $1.06 at the unofficial “street rate”) a day for meals.

Most officers of the 26-strong local police force defected from the regime after the takeover. Suspects are brought before a resistance legal affairs committee, which judges cases or refers them to the NUG. Minor offenders such as drunken drivers can be shackled in stocks for 24 hours before release.

In the center of town, seven sheets pinned to a hut declare the resistance’s township rules. Villagers who “speak in a way that is not acceptable to the public administration body, such as threatening [or] scolding” can be fined or imprisoned. Prosaic rules — register guests, no loud noise after 9 p.m. — precede a warning against cheap methamphetamine pills called yaba.

One notice tries to dispel fears that a new form of tyranny will replace the old, promising that resistance police wielding guns without permission will be punished. Still, hushed voices speak of ill-disciplined fighters throwing their weight about, blurring the line between taxation and extortion. Armed PDF members sometimes demand taxes and expect discounts from local businesses, according to some locals.

Another ousted NLD parliamentarian, Ye Myint Swe, 39, heads the People’s Administration Team (PAT), a local political body formed by the NUG. His team of 21 oversees public services in the rebel-run part of Tanintharyi township, including education (41 schools) and health (six clinics). A handful of shops serve as electricity stations, mainly for charging phones.

Ye Myint Swe says the administration has four sources of taxes: ferry transportation, alcohol sellers, sand and stone construction sites, and mining, the most lucrative. PDF checkpoints operate near mines and tax the tin and lead ores produced, he says.

The Tanintharyi PAT accrued about 45 million kyat in alcohol, ferry and construction site taxes, and 700 million kyat in mining taxes last year, he says. The NUG takes 30% of the tax, the PAT 30% and the resistance forces 40%, he says, adding that the PAT can request extra funds for specific purposes from the NUG.

Theoretically, the NUG splits its share in three — a third for PDF-controlled areas with smaller pools of taxation, a third for its own funding and a third for a regional fund that can be channeled to particular areas in event of a serious conflict. However, resistance sources who want more transparency and documentation about the use of funds question whether the model has been implemented.

The PAT team collects taxes alongside PDF and local militia members. But Ye Myint Swe says he is conflicted about the presence of armed PDF soldiers in populated areas. “In some places, we have PDF for security, but most are in the front-line areas,” he says. “The people sometimes say they sleep better if the PDF are nearby. But I’m concerned it could make the area a target of the regime.”

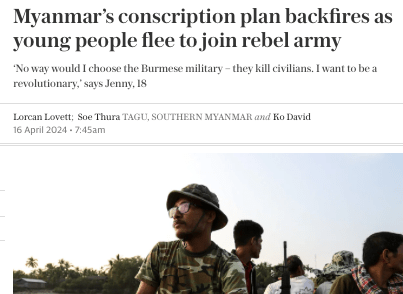

A 2014 census counted 106,853 people in Tanintharyi township. Less than 50,000 remain in the military-controlled area, Ye Myint Swe says, adding that about 1,000 crossed into PDF-controlled territory recently after the regime’s announcement of a fresh conscription drive. He adds that keeping the peace between resistance fighters and the public is crucial. “We need to create the conditions in which we can control our own destiny,” he says. “We’re not defensive anymore. We’re leading the battle, and in every way the junta soldiers are failing.”

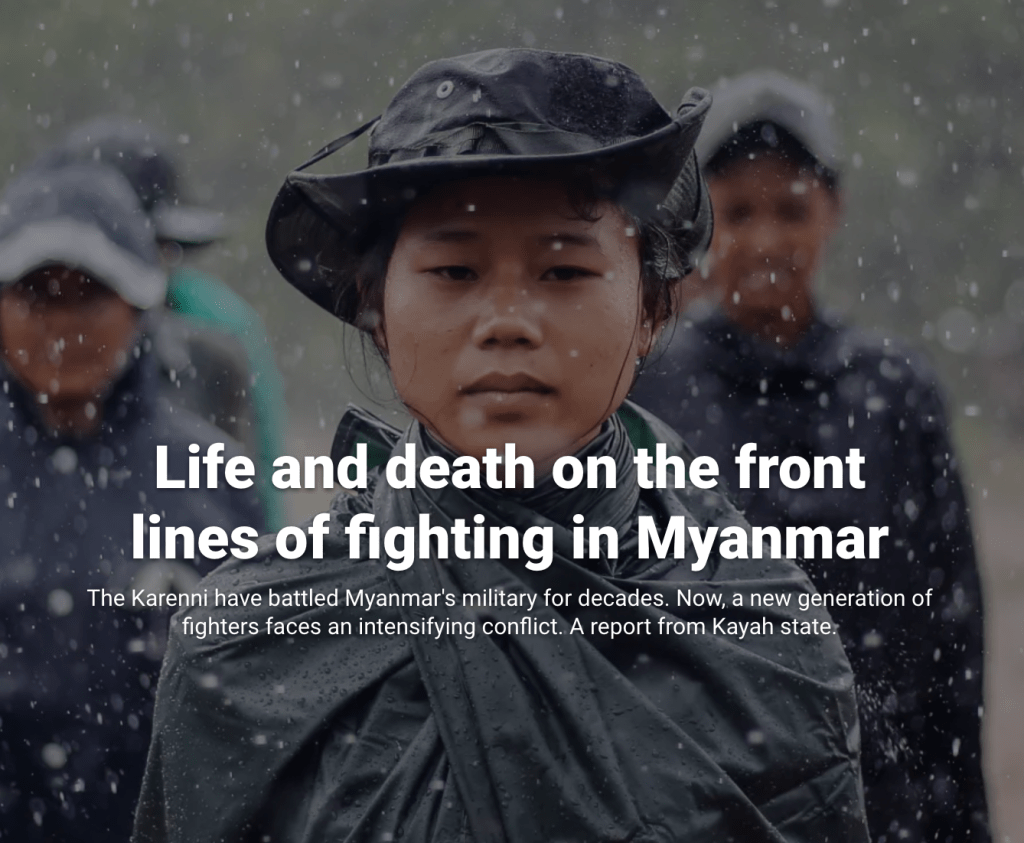

In the three years since the takeover, cooperation between established armed ethnic groups and newer resistance forces has contributed to battlefield success in parts of the country. But in ethnically diverse Tanintharyi, clashing local agendas and deep-seated mistrust have hindered the formation of strong alliances.

Among the armed groups in the region, the PDF and Brigade 4 of the KNU share a delicate relationship. The KNU’s seven brigades have backed the PDFs to varying degrees in different areas, and a resistance source said some battalion commanders in Brigade 4 had trained and helped form resistance forces in Tanintharyi. But other commanders have allowed the military to resupply and rotate troops under the terms of a cease-fire agreed before the takeover.

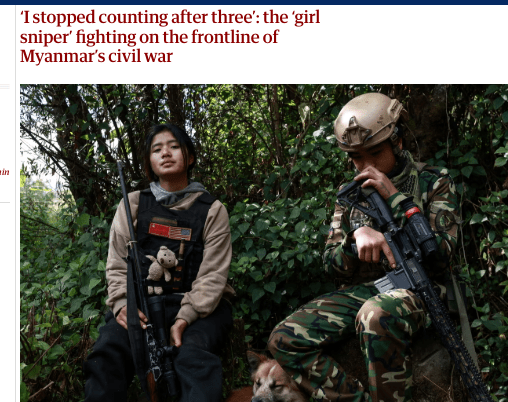

Some local PDF leaders perceive Brigade 4 as overly cautious because of its interests in mining, border trade and other businesses. From Brigade 4’s viewpoint, some PDF forces need better training and closer collaboration with its seasoned commanders. Recklessness takes a heavy toll, particularly on Karen communities — long-standing targets of military aggression.

Crucially, neither side seems willing to concede command during offensives. Still, the Karen forces appear to be toughening their stance against the regime. Brigade 4 captured a military outpost earlier this year. “Now it’s all open warfare against the military,” says a resistance commander, predicting that a clearer anti-regime stance will attract more multiethnic recruits to Brigade 4’s ranks.

Among lower ranks there is camaraderie; some local PDF trainers even wear KNU badges in homage to their trainers. Sharing an adversary — the military — buoys hope for more cooperation. But the relationship is fragile, clouded by uncertainty over the future as the tide of the regime recedes.

Deep in rural PDF territory, about 20 workers hammer and sieve rocks at an open cast tin mine. Nearly half are children, sifting through the jagged debris dynamited by companies operating on the barren, cratered hill. The children lower themselves into a stream and rinse their finds, separating out tin ore and heaping it next to Khin Nge, 53, the matriarch of the mine. “The kids know how to pick the right rocks by the time they’re 10,” she says.

Most of the workers are relatives, says Khin Nge, a grandmother who has worked the mines since childhood. Picking through rocks has worn out her body; she sits and talks and hammers stones on autopilot. Landslides can make the work deadly, she says. But the danger of shootouts eased after Myanmar troops based 8 km away stopped venturing to the site.

“We have to run if the junta soldiers come, but they haven’t been to these mines for over a year,” she says.

Metal traders buy directly from the workers at the mine, Khin Nge says, which allows the laborers to dodge the PDF tax levies. But she is unsure where the tin ore ends up. Her family can earn up to 60,000 kyat daily from the mine, offering whiskey, chicken and candies on palm leaves to appease the mine’s spirit, or nat.

Further up the slope, three middle-aged teachers who refused to work under the military regime labor in the heat. “Our lives have completely changed,” says one.

Back in Le Thit, boat maker Aung Zaw Htay, 38, fears that traditions such as an annual boat race will be lost because of the turmoil caused by the war and the COVID-19 pandemic. Two dragon boats, each carved from a single tree to accommodate 42 competitors, are filled with ants and cobwebs.

For now, Aung Zaw Htay focuses on preserving winning strategies. “Everybody must move in sync,” he says. “If someone is out of step, the team loses.” Amid Tanintharyi’s war against the regime, his words strike a chord.

Interpretation by Soe Thura. Audio translation by Ko David. Photographs by Valeria Mongelli.