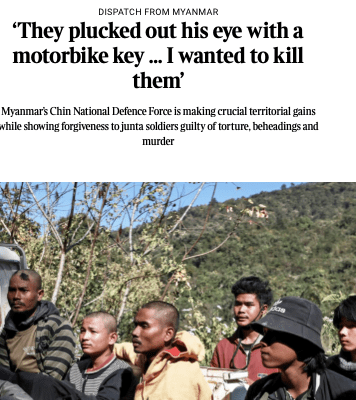

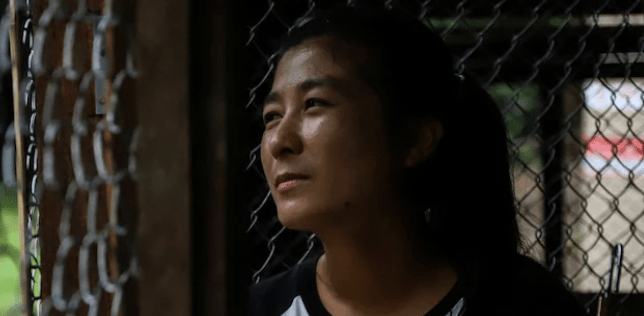

Everyone in the Myanmar resistance knows the brutality of the country’s ruling junta, but even by their standards the cruelty inflicted on Timothy and Isaac was difficult to comprehend.

They were found in the town of Falam in the far west of the country, where a battle is raging between the junta’s forces and the rebels who surround them. The two young resistance fighters, members of the Chin ethnic group, were injured in a skirmish and dragged by their junta enemies to a nearby school.

The next day the Chin fighters took back the building and everyone inside. The bodies of Timothy, 20, and Isaac, 19, were there, mutilated in the most horrible way imaginable. But they also captured the government soldiers who had tortured and murdered the prisoners.

“They plucked out my comrade’s eye with a motorbike key,” said Commander Biak Run Thang, who led the unit of the Chin National Defence Force (CNDF), weeping as he mimed the action. “The other one, they beheaded him.”

Biak Run Thang found himself driving the captured murderers across the mountains to a detention camp for prisoners of war. It was a six-hour journey, but there was just one thought on his mind. “I was furious,” he said. “I wanted to kill them.”

It would have been a simple matter to stop the vehicle, draw his knife and exact revenge. And all over the country, the civil war is forcing ordinary Myanmar people, who until a few years ago had no thought of fighting or torture, to face similar dilemmas.

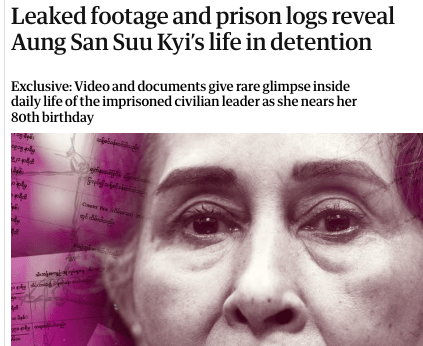

It will be four years on Saturday since the military coup that drove from power the democratically elected government of Myanmar’s democracy leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and since then conflict has gone through terrible evolutions.

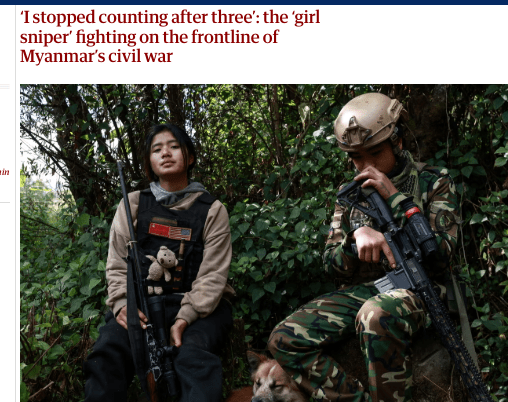

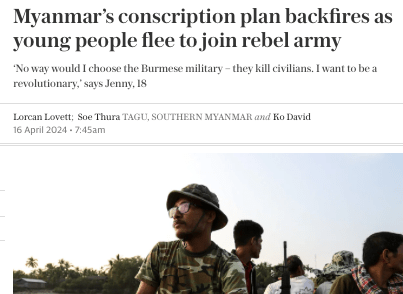

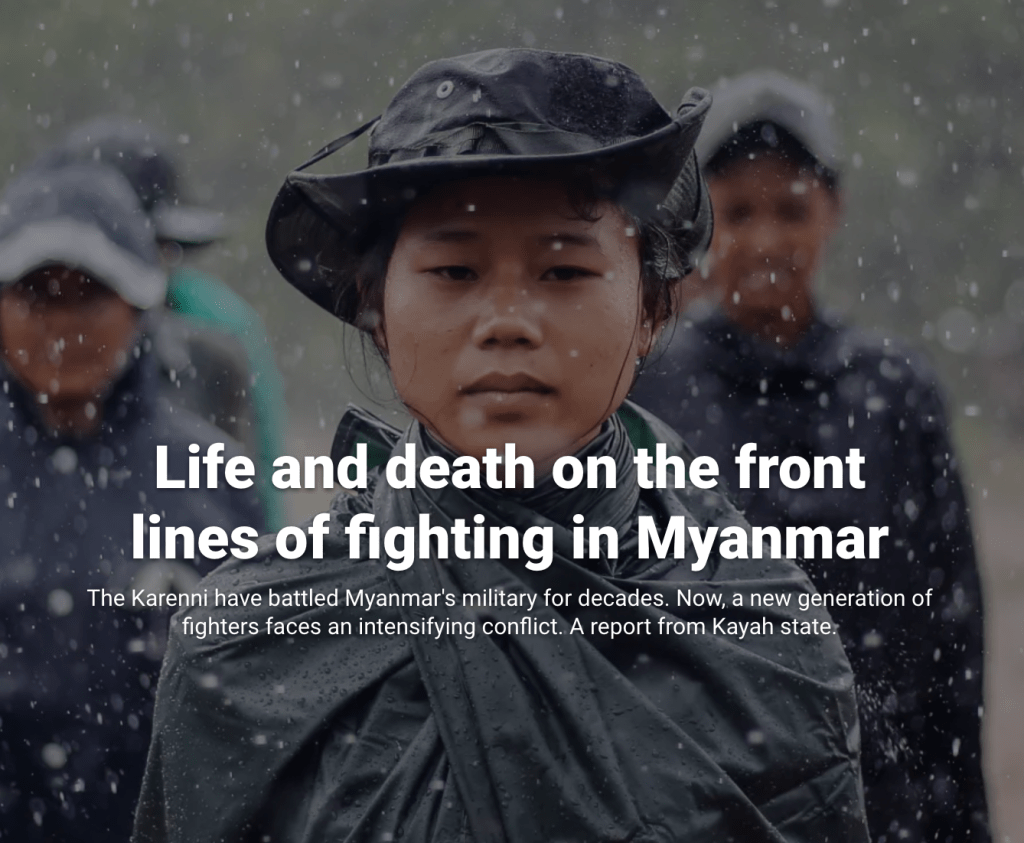

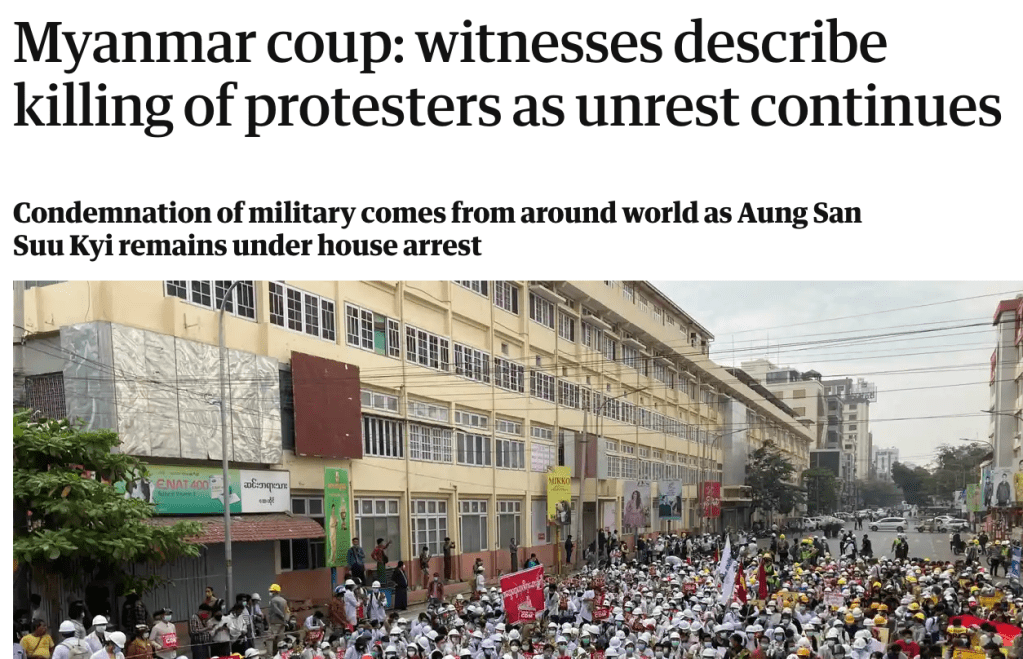

For a few weeks, it was dominated by peaceful anti-junta demonstrations in cities. When these were violently suppressed, they gave way to ragged but bitter clashes between the army and an assortment of regional guerrilla groups and People’s Defence Forces, who fight in the name of the National Unity Government (NUG), a shadow government of deposed democratic politicians.

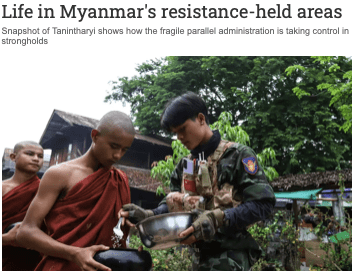

Then the resistance groups joined forces with ethnic armies that have for decades been fighting for regional independence for Myanmar’s borderlands. For a long time they were outgunned and outnumbered by the more numerous forces of the junta leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Then late in 2023 the resistance began to achieve a series of unexpected, decisive and morale boosting victories.

The rebels now hold dozens of towns, and Falam may soon be one of them. Some 600 Chin fighters outnumber and surround a government garrison of 120 who are trapped in the town’s hilltop military base.

The CNDF did not exist before the coup — it is made up of civilians such as Biak Run Thang, a 34-year old manager of a construction site. If it is successful, its offensive — codenamed “Mission Jerusalem” — will drive out the junta from the former capital of Chin State, a predominantly Christian territory on the border with India. According to the CNDF, it would be the first time that a resistance organisation has captured a district centre without support from longstanding ethnic armies.

Unlike the established ethnic forces, who seek to protect their own territorial enclaves, these new fighters have big dreams — of marching on Yangon, the nation’s largest city, and the capital Naypyidaw.

“We will fight until the junta falls,” said Salai Tihau, a senior figure in the CNDF and a 33-year-old former school teacher. “We want to become a standard army with well-trained soldiers. Our end goal is to overthrow the military dictator. Until that is achieved, we will continue to fight.”

However, the junta’s Russian and Chinese fighter jets and attack helicopters, and the resistance’s factionalism and lack of a central authority, are grave obstacles to victory. As the civil war has become more intense and evenly matched, so has the violence, cruelty and sadism of both sides.

More than 6,000 civilians have died during four years of war; nearly 3.5 million people have been displaced inside the country and more than one million driven abroad. The junta stands accused of countless atrocities, many of them involving the indiscriminate bombing of towns and villages with the loss of innocent civilian lives.

Then there is the kind of intimate, small-scale sadism inflicted on Timothy and Isaac. Unsurprisingly, this has provoked similar acts from resistance troops driven to rage and desperation by the torture and killing of their comrades.

“The main perpetrator of atrocities over many decades is the Myanmar military,” says John Quinley of Fortify Rights, a human rights organisation that investigates rights violations on all sides. “As the NUG gains more of a physical presence on the ground, one of their mandates should be to ensure people who commit abuses in the resistance are held accountable.”

The darker reaches of the internet contain sickening films, shot by resistance fighters on mobile phones, of junta prisoners and informers being tortured and killed. This was the choice facing Biak Run Thang as he drove with the captured men who had carved up his friends.

Many of the government troops are victims, in their way — as the junta has come under pressure, it has taken to conscripting recruits who are sent into battle with scant training and no experience. “Our commanders knew nothing of their strength here,” one junta captive in Chin captivity told The Times. “No instructions on what roads to take, no strategy. We could have won these battles before, when we had soldiers who had some experience.”

When they got to the prisoner of war camp, Biak Run Thang’s restraint failed him. He punched the killers, then stopped himself. As a devout Baptist, he remembered Psalm 91: “You shall tread upon the lion and the cobra,/The young lion and the serpent you shall trample underfoot…. with your eyes shall you look,/And see the reward of the wicked.”