Falam Township, Chin State — In the mountains of western Myanmar, photographs of fallen fighters line the wall of a rebel headquarters – an honour roll of some 80 young men, beginning with 28-year-old Salai Cung Naw Piang who was killed in May 2021.

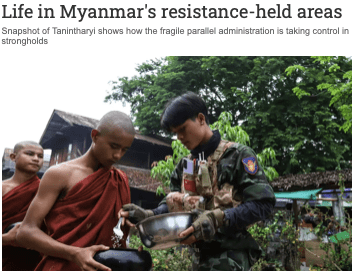

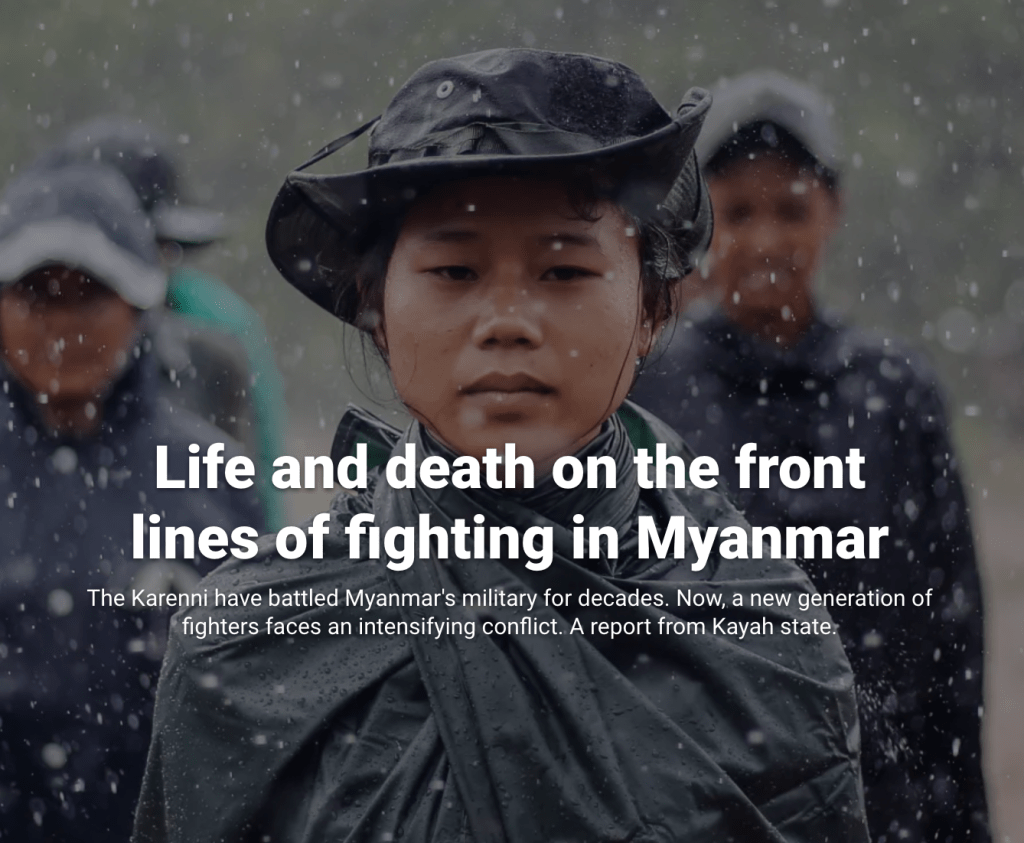

The true toll on the Chin National Defence Force (CNDF) extends beyond this hall and grows as war against Myanmar’s military grinds on in Chin State – a Christian region of the country bordering India where ethnic Chin fighters have expelled the military from most of their territory.

“Even if they don’t surrender, we will go till the end, inch by inch,” CNDF Vice President Peter Thang told Al Jazeera.

Launched in mid-November, the Chin offensive to capture the town of Falam – codenamed “Mission Jerusalem” – has come at a heavy cost. About 50 CNDF and allied fighters were killed in the first six weeks, some buried alive after direct airstrikes by jet fighters on dirt bunkers, Thang said.

He estimated similar casualties among Myanmar’s military, with over 100 troops captured.

“We are facing a difficult time,” he said. “If God is willing to hand over the enemy, we will take it.”

Formed by civilians after the 2021 coup in Myanmar, the CNDF has encircled the military’s last garrison in the former capital of Chin State.

Taking Falam town – Chin state’s former capital – would mark the first district centre captured by the country’s new rebel forces without support from established ethnic armies, according to Thang, who ran a travel agent in Myanmar’s commercial capital Yangon before the coup.

“We’re all newcomers,” he said.

“We have more challenges than others. The military has so much technology. We have limited weapons, and even some of them we can’t operate,” he added.

With the CNDF supported by fighters from 15 newly formed armed groups, including from Myanmar’s ethnic Bamar majority hailing from the country’s central drylands region, about 600 rebels have besieged Falam and the roughly 120 government soldiers who, confined to a hilltop base, depend on supplies dropped by helicopter for their survival.

Unlike established ethnic armies who are fighting to gain more territory for themselves, the rebel forces massed in Chin state aim to overthrow Myanmar’s military regime entirely.

While the CNDF and allies in the Chin Brotherhood (CB) coalition scored previous victories against the military with help from the powerful Arakan Army (AA) to the south in Rakhine State, seizing and holding Falam independently would represent a new phase in Myanmar’s revolution.

The biggest challenge in the battle remains aerial attacks by the military regime.

Operations against the hilltop base in Falam trigger bombardments from the military’s Russian and Chinese jets, along with rocket-propelled grenades, artillery, sniper and machine gun fire.

The onslaughts force rebel fighters to take cover in the abandoned town and plot their next move.

The besieged soldiers once chatted freely with locals; some even married local Chin women, said CNDF commanders. But that all changed when the security forces shot peaceful protesters demonstrating against the military’s ousting of Aung San Suu Kyi’s elected government in 2021.

Mya Thwe Thwe Khaing, a 19-year-old protester, was the first victim – shot in the head by police on 9 February 2021 in the country’s capital Naypyidaw.

Demonstrators fought back, and an uprising was born that has become steeped in blood and the lore of many martyrs.

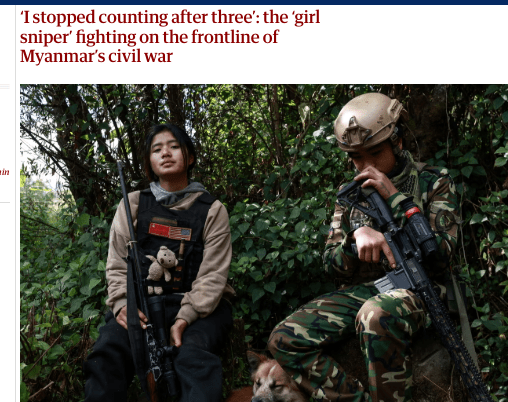

In April 2021, armed with hunting rifles, the Chin launched the first major battle of Myanmar’s uprising in Mindat town, which has since been liberated. Now the rebels are equipped with assault rifles and grenade launchers. They control most of the countryside and several towns, but remain outgunned, as the military entrenches itself in urban centres.

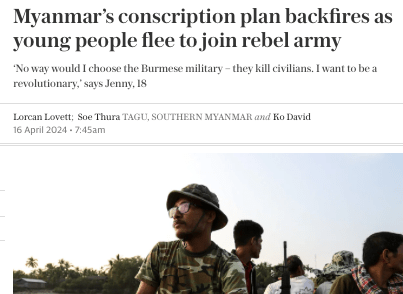

Unable to muster ground offensives from their depleted ranks, the military regime’s generals have turned to forced conscription and indiscriminate airstrikes nationwide.

According to rights group the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, the military has killed at least 6,353 civilians since the coup. With over 3.5 million people displaced inside the country, according to the United Nations, observers predict even fiercer fighting this year.

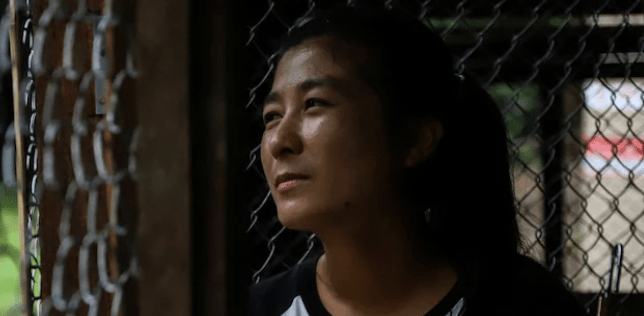

In Falam, CNDF defence secretary Olivia Thawng Luai said spouses live with some of the troops in their hilltop holdout.

“Most soldiers want to leave their base but they are under the commander’s control,” said Olivia Thawng Luai, a former national karate champion. “They aren’t allowed to leave the base or use their phones,” she said.

Another senior CNDF figure, Timmy Htut, said the commander in the besieged base still has his own phone – and they call his number regularly.

“One day he will pick up,” he said. “When he’s ready.”

Attempts by the regime to deploy reinforcements have failed. Helicopters, facing sheets of gunfire, drop conscripted airborne recruits on Falam’s outskirts, ordering them to fight their way in. None have succeeded.

A captured soldier said his unit was dropped in without a plan, and, under heavy fire and pursued by resistance fighters, they scattered in chaos.

“Some died, others ran in all directions,” the soldier told Al Jazeera.

“The headquarters said they couldn’t waste their jet sorties for just a few of us,” he said.

The military, he continued, has lost “many skilful, valuable” soldiers since the coup.

“They gave their lives for nothing,” he said.

“In the end, the military leaders will offer peace talks, and there will probably be democracy.”

Among the displaced people in Falam sleeping under bridges and tarpaulins, a new generation prepares to fight.

Junior, 15, who assists at a hospital camp, spoke from a bomb shelter within earshot of jet bombs.

“I’ll do whatever I can,” she said. “There’s no way to study in Myanmar. I don’t want future generations to face this.”

But the Chin resistance is also grappling with internal division. It has split into two factions: one led by the Chin National Front (CNF), established in 1988, along with its allies, and the other, the CB, comprising six post-coup resistance groups, including the CNDF.

The dispute centres on who shapes Chin’s future – the CNF favouring a dialect-based governance structure, the CB preferring townships. This distinction between language and land determines the distribution of power, and, coupled with tribal rivalries and traditional mistrust, has led to occasional violent clashes among the Chin groups.

Myanmar analyst R Lakher described the divide as “serious”, though mediation efforts by northeast India’s Mizoram authorities show progress.

On February 26, the two rival factions announced they would merge to form the Chin National Council, with the goal of uniting different armed groups under one military leadership and administration.

While welcoming the development, Lakher stressed the process must be “very systematic” and include key political leaders from either side, not only advocacy groups.

“Chin civilians have suffered most,” he said. “Despite liberation, some cannot return home because of this internal conflict.”

Capturing Falam would be “significant”, he said, as nearby Tedim town would then present an easier target, potentially freeing up territory of the CB and strengthening their negotiating position with the CNF coalition.

Lakher estimated over 70 percent of Chin State has been liberated.

“We’ve seen the junta being defeated across Myanmar,” he said. “But pro-democracy forces need unity.”

He said the onus was on the National Unity Government – described as Myanmar’s shadow government – to “bring all democratic forces together”.

“With so many armed groups, there’s concern they’ll fight each other without strong leadership,” he said. “Ethnic areas are being liberated while Bamar lands remain under military control. The revolution’s pace now depends on the Bamar people.”

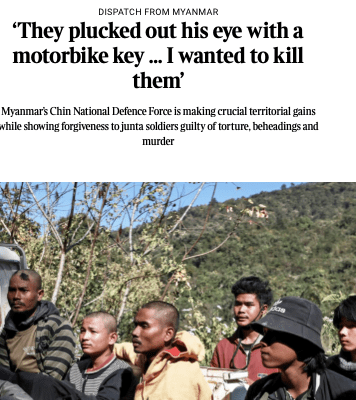

Along the road leading out of Falam town, two trucks loaded with captured regime soldiers drove past Chin’s bombed churches, gardens of mustard leaf, and mothers cradling babies under heavy shawls.

As the trucks crossed paths with resistance fighters heading to the front, the nervous prisoners of war claimed they had been forced into military service.

“You were conscripted five months ago,” a rebel fighter remonstrated with prisoners in the truck.

“What were you doing before then? We’ve been fighting the revolution,” he said.

Another added to the rebuke.

“Count yourselves lucky to be captured here,” he said – and not in the central drylands, where rebels roam unchecked. “None of you would be alive there.”

Before advancing to the front lines of the siege, Chin fighters paused at their comrades’ graves – two ethnic Bamar fighters killed in December’s air raids.

One dropped to his knees and gripped a fistful of earth.

“Come follow us,” he wept to his dead friend.

“We’ll go home together.”